|

|

| |

| |

Karnak Temple

|

| |

Where today thousands of tourists stand in awestruck

silence at Karnak’s gargantuan architecture there once

beat the religious heart of ancient Egypt. The entire

temple complex was formed from three independent

precincts, each of which was enclosed by walls of

unfired mud bricks. At the center lay the gigantic Amun

temple which covered an area of well over 100 ha (247

acres). It was adjoined immediately to the north by the

smaller precinct of Month, the old local deity of

Thebes.

The other neighboring temple of the goddess Mut was

built to the south of Amun temple, and the two were

connected by an avenue of sphinxes. The network of

processional roads on the Theban east bank alone covered

several miles and was flanked by almost 1300 statues of

sphinxes. Archeologists have shown that Karnak’s 2000

year architectural history began in the early Middle

Kingdom and stretched into the Greco-Roman period. Its

intrinsic scale was established by the enormous building

programs initiated by the monarchs of the New Kingdom.

Almost all the pharaohs of this era left their mark on

the imperial temple of Amun in order to honor their

divine father Amun-Re, “King of the Gods.” The complex

has two axes, the main one running in an east-west

direction from the inner sanctum to the first pylon. The

side axis, the cult route to the precinct of Mut, starts

at the fourth pylon and runs south through pylons seven

to ten with their courtyards.

Within the walls of the Amun precinct stands a series of

other shrines and chapels including a temple for the

moon god Khonsu from the Twentieth/Twenty-first

Dynasties and the small temple to Ptah at the northern

enclosure wall whose core was built during the reign of

Thutmosis III. The same king built a temple for the sun

cult directly outside the eastern enclosure wall of the

main temple; a single obelisk (H. 101 ft, 30.7 m) stood

at its center but since 1587 this has decorated the St

John in Lateran Square in Rome. The continual expansion

of the Amun temple necessarily meant the demolition of

older buildings.

The stone from these buildings was then recycled (see p.

329) and provides the basis for our knowledge of temples

in the Middle Kingdom and early Eighteenth Dynasty;

these include such shining examples of architecture as

Senusret I’s “White Chapel” and the great barque shrine

of Hatshepsut, the “Red Chapel.” Ever since Auguste

Mariette excavated at Karnak in 1858 investigations at

the site have largely been carried out by French

scholars. Responsibility for the main archaeological

work and conservation effort has been exercised by the

Centre Franco-Egyptian since 1967. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

The Great

Hypostyle Hall in Karnak |

|

| |

Painted lithography from David Roberts’ “Egypt and

Nubia,” London 1846-1850 Pictures from the 19th century

record how the Great Hypostyle Hall then looked with its

growing piles of rubble, toppled columns and collapsed

architraves.

Extensive damage to the foundations finally led to the

deafening collapse of this famous building on October 3,

1899. Decades were to pass before it was reconstructed. |

|

| |

| |

| |

: |

Ram

sphinxes at the first pylon |

|

| |

Nineteenth Dynasty, ca. 1250 B.C.

The architectural history of the Amun temple began with

a building by Senusret I in the courtyard of the Middle

Kingdom (now destroyed) before advancing west-wards. The

first pylon, dating from the Thirtieth Dynasty, was the

last monumental structure (W. 370 ft, 113 m) to be built

along this axis although it was never completed. The

largest gateway ever built, this pylon interrupted a

long avenue of sphinxes which originally led from the

second pylon of Horemheb to the quay of the temple (with

its great harbor basin and canal connecting it to the

Nile) and which was probably laid out under Ramesses II.

Mounted on high pedestals on both sodes of the cobbled

processional avenue are the figures of so-called cryos

sphinxes combining the body of a lion with the head of a

ram, the sacred animal of Amun. Royal statuettes held

between the paws of each sphinx symbolize the favor and

protection shown by the god.

|

|

| |

|

|

Colossal

figure at the second pylon |

|

| |

Nineteenth Dynasty, ca. 1250 B.C.

The great courtyard behind the first pylon (south tower

with remains of the brick construction ramp) is occupied

by a number of buildings from a variety of eras. The

center is dominated by the gigantic pillared kiosk of

King Teharqo of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Of the ten 69

ft (21 m) high papyrus columns which supported this

structure, only one still stands. It must have been at

the time of this construction work that the avenue of

sphinxes was blocked off and the individual figures at

the sides of the courtyard were put in storage.

This courtyard was constructed during the Twenty-second

Dynasty under Sheshonq I when the area in front of the

second pylon was enclosed by a colonnade.

Behind the north tower of the first pylon is the

tripartite barque shrine of Sety II while the temple of

Ramesses III is integrated into the ensemble on the

southern side of the courtyard and at right angles to

the main axis. A colossal standing figure (H. 36 ft, 11

m) in red granite has been re-erected at the gate of the

second pylon; its fragments were discovered in 1954. The

king is shown wearing a headdress with the double crown

and a short loincloth. His hands, crossed on his chest,

hold the crook and flail of his office; a small figure

of a queen stands at his feet. Although the inscriptions

indicate the owner as being the priest-king Pinudjem I

(Twenty-first Dynasty) the colossus may well have been

carved in the Ramesside era. |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

The

Karnak Temple

In ancient Egypt, the power of the god Amun of Thebes gradually increased during the early New Kingdom, and after the short persecution led by Akhenaten, it rose to its apex. In the reign of

Ramses III, |

|

|

|

|

|

The Valley of the Kings

The tombs of the

Valley of the Kings originally contained many other

items that were transferred to the Egyptian Museum

like the royal belongings of the king that he will

use in the afterlife |

|

|

| |

|

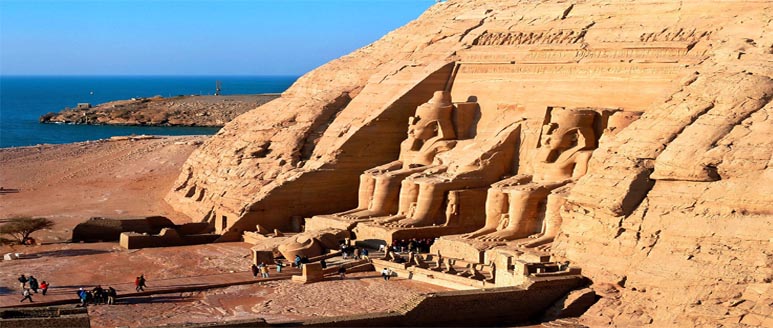

The Queen Hatshepsut Temple

In a spot sacred to the goddess Hathor in the West Bank of Luxor, situated under the foot of one of the huge Theban Mountains, the Queen Hatshepsut has built her mortuary temple that was so fascinating that was called many names in ancient times |

|

|

| |

|

The colossi of Memnon

The Colossi of Memnon. One of the main attractions on the West Bank of Luxor, a landmark which everyone passes on the road to the monument |

|

|

| |

|

The

Luxor Temple

Located in the heart of the modern city of Luxor, the Luxor temple, especially the two colossi of Ramses II situated at the entrance of the temple, has become a land mark of the city. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discover Luxor

Do you have plans to travel to Egypt?

A comprehensive Egypt travel offer – of every type, destination and period in Egypt! In addition, |

Luxor Attractions

Luxor attractions and sightseeing attractions in

Luxor . Book Luxor attraction tours

with Select Egypt |

Luxor Holidays

special discount holiday packages offers for

Luxor travel. We give you tailor made holiday deals for

Luxor travel |

Luxor Tours & Excursions

special discount holiday packages offers for

Luxor excursions. We give you tailor made holiday deals for

Luxor travel |

| Read More >> |

Read More >> |

Read More >> |

Read More >> |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Luxor Hotels

Choose from over 89

Luxor hotels with huge savings. Whatever your budget, compare prices and read reviews for all our

Luxor hotels |

Luxor Map

Luxor was constructed on the ruins of the ancient city of Thebes, the capital of Egypt during the Pharaonic New Kingdom (1550 – 1069 BC). |

Luxor Monuments

The best monuments of

Luxor . Information about Luxor monuments, landmarks, historic buildings and museums in

Luxor |

| Read More >> |

Read More >> |

Read More >> |

|

| |

|

|

|